photo caption: No matter which powered seating components are chosen, the client must be able to operate them independently and safely.

by Susan Johnson Taylor, OTR/L

In a 2017 retrospective study of a large US-based supplier’s database, complex rehabilitation technology (CRT) equipment comprised 86% of their interventions. Of that 86%, 28% were Group 3 power, and 2% CRT Group 2 power.1 Complex powered wheelchairs are applied to clients with physical and functional needs that necessitate individual configuration of the equipment.

The goal of any kind of mobility for anyone is to facilitate participation safely and functionally. Humans just want to be able to get to their activities of daily living (ADLs), functional and social activities, and have enough energy to perform them/enjoy them once they get there. The harder it is to move from place to place, the less likely a person is to want to move to perform the activity. The net result can be simply not participating.2,3

Powered mobility can offer efficient freedom for many CRT clients. In the course of considering this, the clinical team must be able to rule out other methods such as ambulating with or without a device; propelling a manual wheelchair, with or without power assist; or using a scooter. The overriding consideration when looking at these other alternatives is always safety and function for the client in completing their mobility-related activities of living.

First Step

Every CRT recommendation begins with a thorough evaluation by the clinical team. The clinical team focuses on impairments and their limiting effects on performance of activities, social and environmental aspects of the client’s life. This article will provide an overview of considerations for the evaluation, provision of, and training with powered wheelchairs. Different funding sources have different coverage criteria and documentation requirements that are out of the scope of this article. It is best to obtain that information from the client’s rehab technology supplier, the ATP/supplier on the clinical team. However, no matter what the funding, the evaluation and recommendation processes does not change.

The powered wheelchair environment consists of the powered base, the way the client will control and base (input method or methods), and, if needed, powered seating functions, such as powered tilt, recline, elevating legs and seat elevation, among others.4,5,6,7

The Evaluation Process

The first step in any evaluation is to ensure that the client’s positioning has been optimized: therefore, the assumption is made that the client has had a seating/mat evaluation. The client having a stable base of support then allows the clinical team to focus on those skills needed to use and operate a powered wheelchair, including the access to the driving controls and access to the powered seating functions.3

Broadly, evaluation components include:

• The client’s/caregiver’s goals

• Physical considerations

• Vision

• Cognition

• Perception

• Technology tolerance

• Environments and transport

• Use of trial equipment

Client/Caregiver Goals

Obviously, the clinical team needs to understand what the client’s goals and—when applicable—the caregiver’s goals are for mobility. This assists in creating realistic expectations and appropriate matching of the technology to the client. In assessing all of these areas, the access to a caregiver to provide supervision may be the difference between recommending and not recommending a powered wheelchair.

Physical Considerations

Physical considerations encompass the strength, range of movement, and motor control needed to access powered wheelchair input controls and the controls for powered seating components consistently, accurately and safely. One must also consider those who have changing skills over the course of a day, such as those with multiple sclerosis or muscular dystrophy. This can drastically change if the person qualifies for a powered wheelchair as well as the components, such as powered seating, that are interfaced with the powered wheelchair.

Vision

This includes such areas as visual acuity—how well someone can see. Some individuals with visual limitations, such as legal blindness, can successfully operate a mobility device in familiar environments but may need assistance in non-familiar environments. This has to be explored carefully to ensure safety.

Cognition

Safety awareness in all situations in which they will use the powered chair. The therapist must evaluate and consider the client’s attention, memory, ability to plan, as well as decision-making, problem-solving and judgment of safety. For example, if a client does not realize that they should not run into people, or drive off a curb, that has to be considered. As with visual limitations, a caregiver to provide supervision may allow the client to use a powered wheelchair.

Perception

Visual perception includes such abilities as depth perception and visual discrimination. The therapist can ascertain if there are issues with visual perception, or how the person perceives what they are seeing. Individuals with neurologic damage, such as those with cerebral palsy, traumatic brain injury, among other diagnoses, or those who have had a stroke can have alterations in how they perceive what they see, and with what portion of the eye they see.

For example, an individual who has had a stroke that affects their right side may not be aware of what happens on the left side of their body.

Visual perception difficulties can affect the client’s ability to operate a powered wheelchair safely at all, or at least without supervision.

Technology Tolerance

Everyone has varying abilities to understand the use of and care for technology equipment in any aspect of life. For example, some can handle making calls and texts on their cell phones but struggle with other features, while others can fully access all the functionality a cell phone has to offer. It does little good to match a powered wheelchair system to a client/caregiver who are not able to care for it or find it too complex or overwhelming.

Planning, Sequencing

The CRT industry is at a time in history when almost anyone can drive a powered chair. The question should always be, even though we can, should we? The client must have a realistic idea of the amount of equipment, the complexity of the equipment, and complexity of care it requires. A careful examination of this can avoid costly equipment abandonment.9

Environmental and Transportation Access

A home accessibility assessment, done by either the ATP/supplier or the therapist, must be carried out to ensure the powered wheelchair can get into and out of the home, as well as around the home where the client needs to access. Other environments that are key to the client’s participation must also be reviewed.

The powered chair must be transported in the community somehow. The clinical team needs to know what this method/these methods will be. This is particularly crucial if the client is to drive a vehicle from their powered chair, as the chair will need ingress to and egress from the van, and the client will need unimpeded access to the vehicle controls. Also to be considered is the tie-down method for the chair as well as the size of the client plus the chair to be within the weight limit for the ramp/lift.

Use of Trial Equipment

There is no substitute for trialing a powered wheelchair and input methods. Looking at the static ability of a client to move to access controls is far different from layering on the effects of moving through space. This provides the clinical team with information about the motor, cognitive and perceptual skills and reactions to moving through space as well as their ability to handle distractions.

Trialing equipment allows the clinical team, along with the client, to decide upon the best mobility base style, input method(s), and powered seating functions, and how they will be accessed.

Recommendation Process

There are several decisions that must be made. The person must be matched to the seating that provides the best support for driving, the access method must be chosen, powered seating functions must be decided upon—all of which then must go into a powered wheelchair base. The ATP/supplier guides the clinician and client on the equipment combinations that will best meet the client and clinical team goals.

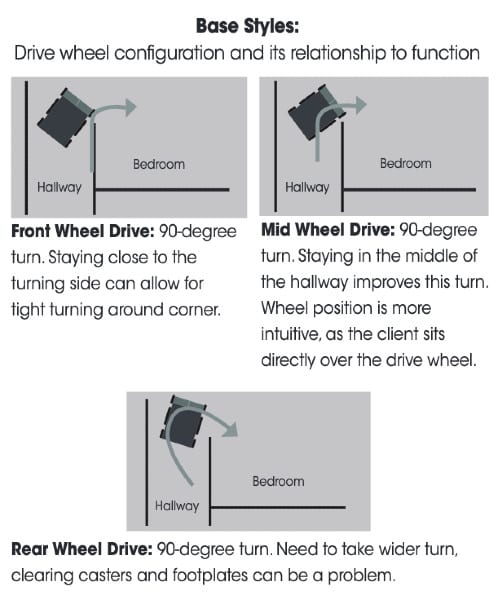

Wheelbase Considerations

There are three types of powered wheelbases: rear wheel, mid wheel and front wheel drive. Each has its unique maneuvering characteristics that relate to client function and accessibility. These should be trialed, as clients have varying levels of skill with each configuration. The following chart provides a view of the differences in these bases.10

Input Considerations and How They are Interfaced

Input options vary from a standard joystick on a standard mountings to individual switches that each represent one direction, to complex eye-gaze systems. No matter what the access method, the client must have access that is reliable, repeatable, and non-fatiguing. The idea behind providing power is after all for efficiency. Remember, the client must be positioned in a stable, functional posture in the seating prior to expecting them to be able to access the driving method.

Some access methods require specialty mounting hardware to optimize the client’s access.

Powered Seating Considerations

No matter which powered seating components are chosen, the client must be able to operate them independently and safely. Basically, this can include operating them with the same access used to drive the chair or by using a separate switch all together. There are many different ways to accomplish this. No matter what the access, especially with powered tilt and recline, the client needs to be able to go all the way down and then all the way back up to their upright sitting posture without losing access to the control input method they are using to accomplish these functions. Perhaps add in the example of hand falling off the arm support/joystick when reclined?

Fitting and Training

The powered wheelchair is of little use to the client without the appropriate fitting and training.10,11 This includes physically fitting the seating, as well as fitting and positioning the access method and programming the chair to match the client’s physical, functional, and perceptual needs. That way, how the chair reacts to the client’s driving matches their needs.

The client who is new to powered mobility will also require “driver’s training” for consistency and safety. One of the most inclusive training websites/programs is the Wheelchair Skills program out of Dalhousie University in Canada, begun over 20 years ago by Dr Lee Kirby.12 A recent study concluded that providing training in foundational powered skills such as maneuvering and backing up statistically improved the user’s satisfaction with the new equipment, to ultimately improve participation.9 Improved participation in whatever the client values, quality of life, is the ultimate goal of powered mobility.

Complex rehabilitation technology in the form of powered mobility is a powerful tool. That powerful tool can only be applied appropriately and safely with clinical team evaluation, partnership, and training. RM

Susan Johnson Taylor, OTR/L, is an occupational therapist who has been practicing in the field of seating and wheeled mobility for 39 years primarily in the Chicago area at the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago Wheelchair and Seating Center (now the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab). Susan has published and presented nationally and internationally. She is both a member and fellow with RESNA, and currently a member of the RESNA/ANSI Wheelchair Standards Committee and the Clinician Task Force. Susan joined Numotion in 2015 and is the Director of Training and Education. For more information, contact [email protected].

References

- Sprigle S, Taylor SJ. Data-mining analysis of the provision of mobility devices in the United States with emphasis on complex rehab technology. Assistive Tech. 2019;31(3) Published online: 05 Jan 2018. Pg 141.

- Cole E. Mobility assessment: the mobility algorithm. In: Lange M, Minkel J, eds. Seating and Wheeled Mobility: A Clinical Resource Guide. Slack; 2018:139-145.

- Taylor SJ. Wheelchair mobility for disabled children and adults. In: Hsu JD, Michael JW, and Fisk JR, ed. AAOS Atlas of Orthoses and Assistive Devices. Mosby; 2008:544-545.

- Miller A. NuDigest: The basics of getting your client in powered mobility. https://www.numotion.com/blog/october-2018/nu-digest-the-basics-of-getting-your-client-in-po. Published: 2018. Accessed: 1/11/2020.

- Miller A. NuDigest: Selecting the right wheelchair configuration for a powered wheelchair. https://www.numotion.com/blog/october-2018/nu-digest-selecting-the-right-wheel-configuration. Published: 2018. Accessed: 1/12/2020.

- Taylor SJ. NuDigest: The importance of properly programmingpowered wheelchairs. https://www.numotion.com/blog/august-2018/the-importance-of-properly-programming-powered-whe. Published: 2018. Accessed: 1/12/2020

- Taylor SJ. NuDigest: Factors to consider then choosing powered seating tilt, recline and standing features https://www.numotion.com/blog/june-2017/nu-digest-factors-to-consider-when-choosing-powere. Published 2017. Accessed: 1/12/2020.

- Babinec M. Powered mobility applications: mobility categories and clinical indications. In: Lange M, Minkel J, eds. Seating and Wheeled Mobility: A Clinical Resource Guide. Slack; 2018:165-177.

- Sugawara AT, Ramos V, Alfieri F, and Battistella L. Abandonment of assistive products: assessing abandonment levels and factors that impact on it. Disability and Rehab. 2018;3(7):716-23.

- Morgan A. Power mobility: optimizing driving. In: Lange M, Minkel J, eds. Seating and Wheeled Mobility: A Clinical Resource Guide. Slack; 2018:179-199.

- McGillivray M, Sawatzky B, Miller W, Routhier F, Kirby RL. Goal satisfaction improves with individualized powered skills training. Disability and Rehab. 2018;13(6):558-561.

- Kirby, Lee. Dalhousie University Faculty of Medicine Wheelchair Skills Program. http://www.wheelchairskillsprogram.ca. Accessed: 01/11/2020.