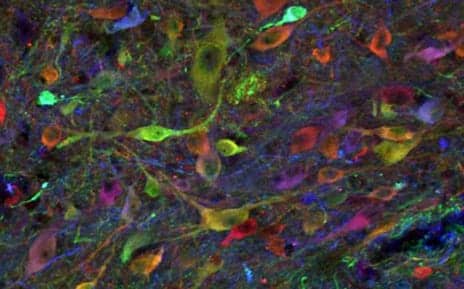

Pictured here is a population of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons in an allogenic, previously injured spinal cord of a pig at 3-and-a-half months. The study was performed by researchers from the University of California San Diego School of Medicine. (Photo courtesy of UC San Diego Health)

In a recent study, researchers describe their successful grafting of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neural precursor cells back into the spinal cords of genetically identical adult pigs with no immunosuppression efforts.

The grafted cells survived long-term, displayed differentiated functionality, and caused no tumors.

In addition, the same cells showed similar long-term survival in adult pigs with different genetic backgrounds after only short course use of immunosuppressive treatment once injected into injured spinal cord, according to a media release from University of California San Diego Health.

The study was published recently in Science Translational Medicine.

“We took skin cells from an adult pig, an animal species with strong similarities to humans in spinal cord and central nervous system anatomy and function, reprogrammed them back to stem cells, then induced them to become neural precursor cells (NPCs), destined to become nerve cells,” explains senior author Martin Marsala, MD, in the release.

“Because they are syngeneic—genetically identical with the cell-graft recipient pig—they are immunologically compatible. They grow and differentiate with no immunosuppression required,” adds Marsala, professor in the Department of Anesthesiology at UC San Diego School of Medicine and a member of the Sanford Consortium for Regenerative Medicine.

In their study, researchers grafted NPCs into the spinal cords of syngeneic non-injured pigs with no immunosuppression. The researchers found that the NPCs survived and differentiated into neurons and supporting glial cells at all observed time points. The grafted neurons were detected functioning seven months after transplantation.

They then grafted NPCs into allogeneic (genetically dissimilar pigs) with chronic spinal cord injuries, followed by a transient four-week regimen of immunosuppression drugs. They found similar results with long-term cell survival and maturation, the release continues.

“Our current experiments are focusing on generation and testing of clinical grade human iPSCs, which is the ultimate source of cells to be used in future clinical trials for treatment of spinal cord and central nervous system injuries in a syngeneic or allogeneic setting,” Marsala states.

“Because long-term post-grafting periods—one to two years—are required to achieve a full grafted cells-induced treatment effect, the elimination of immunosuppressive treatment will substantially increase our chances in achieving more robust functional improvement in spinal trauma patients receiving iPSC-derived NPCs.”

“In our current clinical cell-replacement trials, immunosuppression is required to achieve the survival of allogeneic cell grafts. The elimination of immunosuppression requirement by using syngeneic cell grafts would represent a major step forward,” concludes co-author Joseph Ciacci, MD, a neurosurgeon at UC San Diego Health and professor of surgery at UC San Diego School of Medicine, in the release.

[Source(s): University of California San Diego Health, Newswise]