|

The most common first words uttered by my patients are “I had no idea physical therapists could treat this problem, but at this point, I’ll try anything.” These women have pelvic floor muscle dysfunction (PFMD). They present with varying diagnoses, ranging from stress and urge incontinence and urgency/frequency of urination, to myofascial pain and chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Unfortunately, even though their problems may stem from the muscles of the pelvic floor, it often takes years from the initial onset of symptoms to the time the patients are referred to a physical therapist that specializes in the treatment of PFMD.

Often women with urinary problems or pelvic pain go through a multitude of tests, medications, physician appointments, and sometimes surgery without satisfactory outcomes. Medications and/or surgery certainly has a place in treating severe prolapse of the bladder, uterus, or rectum; overactive bladder; and certain causes of pelvic pain such as endometriosis. But sometimes the opportunity for significant improvement or resolution of the patient’s symptoms is overlooked. The missing piece of the puzzle is the treatment of weakness or spasm of the pelvic floor muscles.

The general public knows physical therapists treat muscle problems, but many do not realize the pelvic floor muscle group even exists, let alone that PTs treat “down there.” Those who are sent to physical therapy were fortunate enough to meet a physician with an understanding of how PFM dysfunction can affect the bladder and/or cause pelvic pain. Ignorance of the benefits of PT cannot be blamed on the physician. We, as physical therapists, need to be part of the education process. By continuing our research efforts and marketing our unique talents in the rehabilitation of the pelvic floor muscles, we can educate physicians and the general public alike.

MILLIONS EXPERIENCE INCONTINENCE

And what a huge market it is. The National Association for Continence estimates that 25 million Americans experience transient or chronic urinary incontinence.1 In 1996 the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research published Clinical Practice Guidelines on Urinary Incontinence in Adults.2 It estimated that 11 million American women experience incontinence, and one in four adults age 30-59 have had an episode of urinary incontinence. Issues involving pelvic floor muscle dysfunctions are common, but not discussed between patients and their physicians often enough. Many women assume leaking urine or urinary urgency/frequency is part of the normal aging process and/or side effects of childbearing, but it is not. A “little inconvenience” now can lead to major quality-of-life issues later in life. During their initial PT evaluation, patients describe these common themes: “I will not leave the house unless the location of all public bathrooms is known”; “I have had to put off dreams of traveling during my retirement years”; “I cannot risk flying across the country to see my new grandchild because I might not be able to get to the bathroom on the plane in time”; “I have been getting in trouble on the job because I always have to run for bathroom breaks”; “I cannot have intercourse with my husband because of increased pain/ urgency”; “I cannot exercise because it increases the pain/urgency/leaking”; and “I have to run to the bathroom every hour. I plan my life around it.”

During the first visit, each woman’s unique functional problems and goals are discussed. Then, a good deal of time is spent educating the patient on the basic anatomy of the pelvic floor and urinary system. Imparting this information is vital to the patient’s understanding and acceptance of treatment. Because people learn in different ways, I use a variety of methods to educate including a model of the pelvis with muscles, diagrams, books, and sometimes a video. An easy-to-understand, fun, and educational book on the subject is Womens Waterworks, Curing Incontinence by Pauline Chiarelli, PhD.3 In addition, I use a good video on the topic, Treating Urinary Incontinence—A Guide to Behavioral Methods, by Family Health Media.4 These resources reinforce normal bladder/muscle function and behavioral changes such as proper diet, exercise, relaxation techniques, and healthy bladder habits. Sometimes, I recommend that a patient read A Headache in the Pelvis5 when she is experiencing urgency or pain syndromes.

Basically, two types of pelvic floor muscle dysfunctions cause very different problems. Below are discussed common findings and treatments associated with the weak pelvic floor and the tense pelvic floor.

STRESS INCONTINENCE

Women presenting with stress incontinence complain of urine leaks associated with a cough, sneeze, change in position, or lifting. These women tend to have a weak pelvic floor. An internal muscle examination is done during the PT evaluation. The patient is asked to perform a PFM contraction, and its strength is assessed. Often those with stress incontinence have significant weakness of the PFM. It sometimes takes quite a bit of verbal and tactile cuing before the patient can elicit a contraction of the correct muscle group. Significant substitution patterns such as squeezing of the gluts, hip adductors, and abdominals, and holding of the breath are commonly seen.

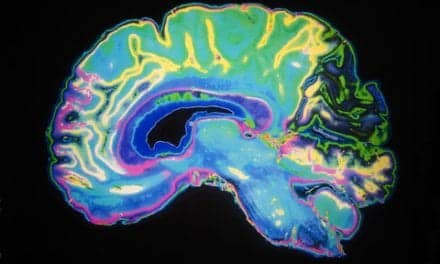

Various forms of biofeedback training benefit the patients by helping them find or “feel” their PF muscles. PTs can use surface EMG over the posterior PFM or an internal electrode placed vaginally or rectally to provide feedback. The patients see their baseline resting tone on a computer screen and watch the graph rise when they correctly perform a PFM contraction. The PT provides verbal cues such as “pull your muscles up and in as if to stop the flow of urine midstream or to stop from passing gas.”

Simple and relatively inexpensive items can be used in the privacy of the patient’s home. Vaginal weights or cones can be used to provide the patient with a sense of where to squeeze. If the correct muscles are not employed, the weight may slip out of the vagina. Also available is an intravaginal plastic probe for the instruction of correct pelvic floor contractions in women. If the patient correctly performs a PFM contraction, a visible rod that extends from the internal probe will tilt downward; if the woman bears down instead, the end of the probe tilts upward. Perineometers are devices that incorporate an internal pressure probe with a handheld pressure gauge to give feedback on the strength of the contraction.

|

| An electromyography system monitors a patient’s attempt to reduce PFM resting tone. The graph indicates difficulty “letting go” after muscle contraction. |

If absolutely no contraction is obtained, the PT may decide to try internal electrical stimulation to elicit a contraction of the PFM and provide the patient with a means to locate and activate the correct muscle group. There are home electrical stimulation units that can be rented or purchased. Insurance sometimes will pay for a unit if a documented 4-week trial of PFM exercises has failed.

Once a woman can contract her muscles independently, adherence to the home exercise program is essential. She is taught to slowly increase the length of the squeeze and repetitions per day, building up to 30 to 80 contractions a day. The patient learns to incorporate quick contractions and up to 10-second holds to work both slow and fast twitch fibers. Simply progressing positions from supine to stand increases the workload to the PFMs for further gains in strength.

Patients are taught to use the PFM functionally. Squeezing before one sneezes, coughs, or lifts will help reduce incontinence episodes. Women with weak PFMs who have a consistent contraction of the correct muscle group during the initial evaluation often need to be seen for only two or three treatments over the course of 3 to 4 months. On return visits, functional progress is assessed, the bladder diary is reviewed, and the home exercise program is advanced.

URGENCY, FREQUENCY, AND PAIN

Conversely, women who present with urgency/frequency, urge incontinence, or chronic pelvic pain syndrome may have a very different PFM dysfunction. They tend to have tense pelvic floor muscles. These women symptomatically feel like they have frequent urinary tract infections and often are prescribed antibiotics over the phone, when, in reality, if a urine culture were obtained, it would be negative. Sometimes PT treatment to normalize the tone in the muscles of the pelvis relieves the symptoms of urgency or pelvic pain.

Muscular trigger points are commonly found in the quadratus lumborum, iliopsoas, abdominals, levator ani, obturator internus, and hip adductors, among others. These patients are typically unaware they chronically contract their pelvic floor, gluteals, hip adductors, and/or abdominals.

What started this holding pattern? It may have begun with muscle guarding due to postsurgical pain, infection, or trauma. It can be simply that when these women experience stress, they unconsciously tense the pelvic floor and surrounding muscle groups. These tense muscles develop trigger points, and tend not to contract or relax appropriately. This compromises blood flow and irritates nerves in the area.

Treatment can include myofascial release internally (vaginally and/or rectally) and externally to the involved tissues, posture training, hip stretches, visceral mobilization, electrical stimulation, and ultrasound. Diaphragmatic breathing is just one of many relaxation techniques used to calm the sympathetic nervous system and increase the patient’s awareness of tension in their body. Surface EMG with biofeedback can be used to teach the patient to improve their muscle function.

This is not the type of patient who should be doing PFM exercises throughout the day as it may exacerbate her condition. The initial focus is on relaxation and attaining proper muscle function and proper body alignment. Strengthening will come later. Instruction on calming urinary urgency, changing diet, avoidance of straining while urinating, and normal bladder function is appropriate for this group. Treatment is generally once a week for 12 or more visits.

Fortunately, for both the “weak” and the “tense” PFMD patient, options are available for diagnosis and treatment of symptoms, which can significantly improve quality of life for the patient. With the proper diagnosis, referral, and treatment, PFMD patients stand to gain great strides against bothersome urinary symptoms and sometimes significant pain and discomfort. Given that PTs are experts in the treatment of muscular dysfunction, our knowledge can successfully be applied to resolve incontinence and pain from pelvic floor muscle dysfunction. Word of mouth is the best referral system, and women talk to women. We just need to get the word out.

Jill Dubbs, PT, is a women’s incontinence specialist at Lakewood Hospital, Lakewood, Ohio.

References

- The National Association for Continence. Available at: www.nafc.org.

- Overview: Urinary Incontinence in Adults, Clinical Practice Guidelines Update. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; March 1996. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uiovervw.htm.

- Chiarelli P. Womens Waterworks: Curing Incontinence. For further information, contact George Parry, 14 Magin Crescent, Wallsend, NSW 2287 Australia.

- Treating Urinary Incontinence—A Guide to Behavioral Methods for Patients and Caregivers. Charlottesville, Va: Family Health Media; 1997. For further information, contact Family Health Media, PO Box 1842, Charlottesville, VA 22903; (800) 366-3641; www.FamilyHealthMedia.com.

- Wise D, Anderson R. A Headache in the Pelvis: A New Understanding and Treatment for Prostatitis and Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndromes. 3rd ed. Occidental, Calif: National Center for Pelvic Pain Research; 2004.