Solutions for safe patient handling should be easy to use, time effective, and supported by facility management and caregivers.

This is the second installment of a three-part series addressing a progression of equipment/durable medical equipment (DME) instrumental in helping patients achieve standing and a return to walking. The first installment in the November/December issue discussed standing frames, and the third will explore body weight support units. Although the article does not cover the entire scope of the topic, the series itself contributes to the body of knowledge for therapists who are not routinely advocating for or utilizing these devices.

Safety for the patient and safety for the health care professional: these two goals were the “necessity” that led to the invention of the patient lift device. The initial design for the sling lift to support patients during transfers was patented in 1955. Today, there are thousands of patient lifts in use across the United States, in nursing homes, adult foster care homes, and patient residences. While the common goal of patient and staff safety may be true for all lifts, their approach, design, and cost are quite varied. This article will address the various indications, types, pros/cons, and nuances of patient lifts.

MOBILE LIFTS

Mobile lifts are commonly used with a variety of patient diagnostic groups (Table 1). Those who use lifts commonly use them for life, but the device also can provide safe mobility during a period of recovery from stroke, complex orthopedic/fracture, or incomplete spinal cord injury, or be used to support temporary precautions in recovery of weight bearing (fracture, pressure/ulcerative lesion in the lower extremities). In rehabilitative settings, patients may use a lift while recovering functional independence, when too fatigued, when medical precautions indicate, or if staffing ability/availability makes a transfer unsafe.

Many hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and nursing homes have adopted “zero” or “no lift” polices for the safety of both patients and staff. Tom LeRoy, PT, Maine Medical Center, an ergonomics expert, leads the policy and application efforts of such programs. LeRoy says, “Assistive technology is critical for dependent patients. That technology can be very simple or more technologically advanced. The art of safe patient handling is choosing the right devices/methods given the environment and the need. Solutions need to be easy use, time effective, and strongly supported by management and the front-line caregivers. The safe patient handling program must be more than equipment. Education, problem solving, and accountability are all critical components to success. Many staff undervalue the effort of bed mobility, which is the most frequent patient mobilization.”

TABLE 1: Most common conditions indicating patient lift use

- Quadriplegia

- Severe brain injury (stroke, traumatic, congenital)

- Weight-bearing precaution (orthopedic or integumentary)

- Amputation

- Functional dependence due to morbid obesity (bariatric)

As LeRoy alludes, health care professionals benefit from the use of patient lifts as well. These devices offer an exceptional mechanical advantage and a ready hand when qualified/trained staff are unavailable. Used correctly, a mobile lift can help reassure a fearful patient who is overweight or in pain. It is combinations such as these—fearful, overweight, painful, or weak patients—that are the most appropriate applications for all involved.

The Hoyer lift has been nearly synonymous with patient lift devices for years, but there are other options and indications. The four main categories of patient lifts are: mobile floor lifts, ceiling, wall, and stand-assist. With the exception of stand-assist lifts, most models of the other three types of devices operate using a sling, which provides an opportunity to safely surround the patient while providing access for toileting and hygiene.

The scope of this article is restricted to the basic educational points of lift systems. It should be noted, however, that one could consider the subtype standing lift. This category could include recliner-chairs as well as power wheelchairs that assist patients to stand, then operate/propel in the upright standing position.

FLOOR OR MOBILE LIFT

ADVANTAGES

A mobile lift can be quickly wheeled to fit almost any transfer situation, including retrieving a patient from the floor. The sling setup allows for toileting and hygiene, and provides a non-weight-bearing solution for transfers. The crane-like setup with a base can be fit under many surfaces and adjusted (width), allowing for car transfers, for movement from one room to another, or even for imaging and tight spaces.

DISADVANTAGES

Mobile lifts can be difficult to maneuver on carpeting, over thresholds, or with bariatric patients. A manual crank and the work needed to propel the mobile lift place a greater workload on staff than electric or battery-powered options.

CEILING LIFT

ADVANTAGES

Ceiling lifts reduce the burden on staff to two tasks: application of the sling and directing the patient along the track once lifted. No physical lift or manual crank should be needed to operate the device.

DISADVANTAGES

Ceiling lifts are limited by track application, which will restrict car transfers and access to any part of a facility that does not have a track installed. If a patient falls outside of track access, the ceiling lift is of no use for one of the most difficult situations. Cost is a main concern with ceiling lifts. The lift and tracking options to adequately cover a home or facility can be very expensive. Additionally, installing a track may require building reinforcement.

STAND-ASSIST

ADVANTAGES

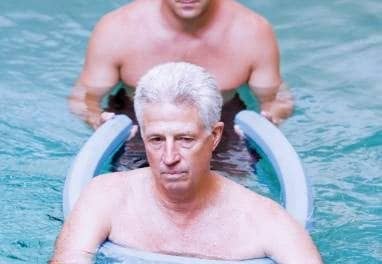

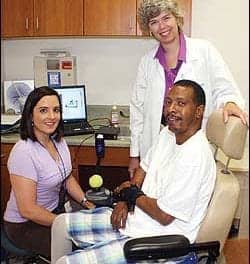

A stand-assist can be more rehabilitative in nature and complement a patient’s return to upright mobility, in contrast to a dependent sling. Most stand-assist lifts do not employ a sling and can be wheeled from place to place with the patient upright.

DISADVANTAGES

A stand-assist lift commonly requires patients to sit up, without assistance, prior to coming fully upright. Patients are not suspended in a fashion that helps with toileting (no sling employed). Stand-assist lifts do not provide a weight-bearing aid, may be difficult for a bilateral or unilateral amputee to use, and can be challenging to move with bariatric patients or on carpeting.

WALL LIFT

ADVANTAGES

Wall lifts require less space and provide a reliable mechanical option for difficult transfers. They are often employed for showers. The device and track can be more readily installed than a ceiling lift due to physics and building retrofit considerations.

DISADVANTAGES

Clearly, a wall lift is installed on one wall. Therefore, the lifts have a limited range or access. The lift device can be moved from one track to another, yet it is still an expensive purchase.

On a related note, wall lifts, stand-assists, and all other types of mechanical lifts are commonly used for bathing, hygiene, and dressing. Complementary DME and home adaptations for these tasks should be considered when purchasing the right lift. These adaptations often include grab-bars, floor to ceiling transfer poles, shower chairs/benches, and bedside commodes.

When purchasing a device, considerations include most common patient subtype/diagnoses served, budget, as well as space available in common transfer areas. Many new and existing facilities are being fitted with tracking systems to allow lift systems to be dispatched to patient rooms on an as-needed basis.

None of these devices provides a solution for every scenario, but each has versatility and can be adapted readily. The worst decision regarding patient lifts is to not have one when you are in need.

Mike Studer, PT, MHS, NCS, CEEAA, is a full-time clinician at Northwest Rehabilitation Associates, Salem, Ore. He is a board-certified neurologic clinical specialist and certified exercise expert for aging adults. Studer has been a PT for 21 years and is the current Chair of the Geriatric Section—APTA Balance and Falls Special Interest Group. For more information, contact .

![Patient Lifts: Balancing Safety with Recovery[Part Two of a Three-Part Series About Standing Systems, Lifts, and Body Weight Support Units]](https://rehabpub.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/2012-03_04-01.jpg)