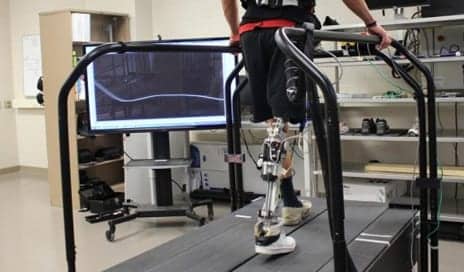

Powered prosthetics are programmed so that the angle of the prosthetic joints—the knee or ankle—while walking mimics the normal movement of the joints when an able-bodied person is walking. (Photo courtesy of North Carolina State University)

Biomedical engineering researchers at North Carolina State University (NC State) and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have developed an algorithm that enables powered prosthetics to tune themselves automatically.

According to a media release from North Carolina State University, powered prosthetics are tuned by a prosthetics expert so that the angle of the prosthetic joints—the knee or ankle—while the patient walks mimics the normal movement of an able-bodied person. However, powered prosthetics need constant re-tuning, as changes in a person’s weight or gait could affect the prosthesis’s ability to achieve a “natural” joint angle.

Helen Huang, PhD, lead author of a research paper about the work, and her team addressed this problem by developing an algorithm that could be incorporated into the software of any powered prosthesis to automatically tune the amount of power the prosthetic needs in order for a patient to walk comfortably, the release notes.

“For example, the algorithm could provide more power to a prosthesis when a patient carries a heavy suitcase through an airport,” says Huang, associate professor in the biomedical engineering program at NC State and UNC-Chapel Hill, in the release.

The algorithm works by taking into account the angle of the prosthetic knee while walking, and adjusts the amount of power the prosthesis receives in real time, according to the release.

“In testing, we found that the computer—using the algorithm—performed better than prosthetists at achieving the proper joint angle,” Huang says in the release. “So we know our approach works. But we’re still working to make it better.”

The research paper was recently published in Annals of Biomedical Engineering, according to the release.

[Source(s): North Carolina State University, Science Daily]