Combined expertise from a variety of disciplines helps shield patients at risk for pressure ulcers.

Pressure ulcer prevention and healing presents a serious challenge with many facets and the need for solutions that are innovative and multilayered. In the absence of collaborative efforts, both patients and institutions are at great risk, and this is particularly true for institutions that treat the most medically complex individuals. Using a creative cluster of interdisciplinary teams, we were able to improve pressure ulcer outcomes at Magee Rehabilitation Hospital, Philadelphia.

A UNITED FRONT

Historically, at this facility, each clinical discipline assessed skin integrity within the context of its scope of practice and the patient’s overall health condition and focused efforts on skin preservation. This was sufficient for many years. However, during the last 8 to 10 years, the acuity of patients changed dramatically. The facility serves a neurologically impaired population with extremely high acuity and a high number of persons with spinal cord injury (SCI). Sixteen percent of Magee Rehabilitation Hospital’s entire patient population and 27% of its patients with SCI have pressure ulcers at admission. Despite great intentions, cross-disciplinary collaboration related to skin protection was difficult. A Wound Leadership group was appointed to coordinate these disparate efforts, review data, and provide a centralized administrative reporting mechanism. This created a unified front to achieve a mutual purpose.

As small groups and task forces were assembled, we began to understand the nuances and complexities of the skin care management for these patients. It also became understood among the members of these groups that none of the factors could be managed successfully by any one discipline. Through discussions with various stakeholders, a vision was developed: to eliminate preventable acquired pressure ulcers within our setting and ensure that those pressure ulcers present upon admission would be healed to the best of our ability.

While leadership in these teams was critical to mobilize ideas and foster engagement, it was also recognized that the inclusion of front-line staff who provide direct patient care was instrumental to the success of the mission. Setting up collaborative teams to identify and address known and potential risk factors proved to be a key starting point. As expected, recurring themes began to emerge through discussions about what was observed on the units, what was read in the literature, and what experience had made evident.

We learned to appreciate how detrimental the skin response to moisture and bowel incontinence can be when a patient is already severely compromised nutritionally, unable to move, and unable to lie with the head of the bed below 30 degrees due to the use of mechanical ventilation. We realized we needed to identify these patients at critical risk much sooner. We assembled an early intervention interdisciplinary group that meets daily to address bowel management concerns for patients at a heightened risk for skin breakdown. Nurses, a dietitian, a pharmacist, medical staff, certified wound ostomy continence nurses (CWOCNs), and therapists convene to review factors that might cause bowel issues and make adjustments to address them proactively.

Early assessment led to prompt patient-centered interventions. Eventually, these discussions evolved to include a review of newly noted pressure ulcers that were at stage one, and any worsening skin issues among our inpatients.

Interdisciplinary team problem-solving resulted in several actions including:

• review of a standardized pressure ulcer risk assessment tool

• use of a standardized bowel consistency description tool

• a discussion of equipment trials and modifications

• targeted patient education

• adjustments in tube feeding regimens

• adjustments in medication regimens

• alterations in therapy programs

• determination of safe timeframes to be seated in a wheelchair.

To complement daily meetings, weekly interdisciplinary wound rounds enabled CWOCNs and therapy staff to view the wounds together. Rounding discussions led to temporary limitations of therapeutic activities that were considered “high risk” for causing skin breakdown or limited wheelchair sitting time until ideal seating systems could be established. Discussions also included nursing staff and respiratory therapists to evaluate bed positioning that would promote respiratory stability while minimizing excessive pressure and shearing forces on the coccyx and sacrum, known to increase as the head of the bed is raised greater than 30 degrees.

ANTICIPATION AND RESPONSE

Housewide, a Skin Champion program was initiated to complement other initiatives and to ensure that best practices related to pressure ulcer prevention were utilized every day across all shifts and within all units. The program was initiated by bringing together a core group of empowered frontline clinical staff (therapists, therapy aides, nurses, nursing assistants, and a physician) who were invested in raising the level of urgency about pressure ulcer prevention. Skin Champions, in their defined roles, promote the authentic collaboration of clinical staff across all shifts and floors with the goal of driving a culture change that assures positive and sustainable outcomes related to the team’s common purpose of pressure ulcer prevention. Actions included: consistent demonstration of evidence-based practice for skin protection with patients, provision of education about skin protection to patients and families, and serving as a resource for other frontline staff in the direct care of patients.

The facility also implemented an inpatient seating clinic staffed by an occupational therapist, a physical therapist, and a technician with clinical expertise in equipment prescription. Because medical risk factors were not part of a traditional PT or OT evaluation (eg, bowel incontinence episodes, increased moisture, poor nutrition, the use of multiple antibiotics that can lead to loose stools), interdisciplinary collaboration provided a more comprehensive picture of the patient. From a therapy perspective, this “glimpse” was helpful in raising the level of attention paid to a patient’s positioning in the wheelchair and/or the level of caution used when considering activities that could place the skin at increased risk for breakdown. Working closely with the primary clinical team and the CWOCNs to evaluate each patient’s posture and skin health in order to set up an ideal seating system as soon as possible after admission has become the goal of the seating clinic.

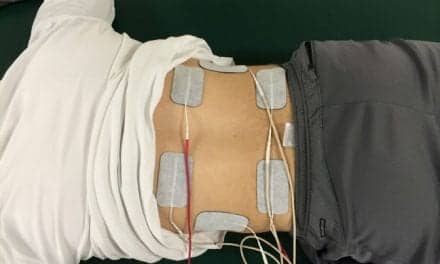

One tool that is used consistently by Magee Rehabilitation Hospital’s clinicians is a pressure mapping system. This device measures the amount of pressure placed on the skin during an activity or within a specific seating system. By placing a thin mat with sensors between the patient and the weight-bearing surface, the therapist is able to obtain a reading for the amount of pressure placed on different areas of the patient. A computer screen displays a corresponding colored visual image that indicates high and low pressure areas. This helps a clinician determine whether pressure is evenly distributed or if there are concerning areas of increased pressure. It also can be used to teach patients about the importance of sitting posture and weight shifts to the integrity of their skin.

In collaboration with CWOCNs and primary clinical teams, the therapists in the inpatient seating clinic evaluate patients and then select specialized equipment for seating systems and bed surfaces that distribute pressure appropriately. There are many options for seating systems (seat backs, cushions, and headrests) that promote proper positioning, optimal pressure distribution, and skin protection, including cushions with air, gel, foam, or combinations. With patients at high risk for pressure ulcers, air or combination cushions have been used to allow airflow and minimize moisture buildup underneath a patient’s buttocks and posterior thighs. Gel, foam, or combination cushions also have been used because they offer multiple positioning options to accommodate people with skeletal deformities that may negatively impact proper seating and positioning.

In our experience, appropriate bed surface selection for a patient at high to moderate risk for skin breakdown is imperative. There are two categories of specialized bed surface systems to consider. Group I support surfaces are preventative and classified as pressure reducing. Group I support surfaces are indicated for patients who have limited mobility and any pressure ulcer on the trunk or pelvis. These include dry pressure mattresses and gel or air overlays. Group II support surfaces are therapeutic and are classified as pressure redistributing. Group II support surfaces are indicated for patients who have multiple stage 2 ulcers, large stage 3 or stage 4 ulcers on the trunk or pelvis, or a myocutaneous flap surgery in the last 60 days. These include low air loss/alternating pressure mattresses and nonpowered dry flotation overlays.

Positioning patients on these surfaces is important to skin health. Wedges can be used to assist with pressure distribution, and repositioning slings can be used to assure safe position changes and prevent shearing while maintaining end-user safety. Equipment selections should be made with consideration of feedback from all stakeholders. Ongoing evaluation and review of products continues to be a key to ensuring selection of the best available options for patients. Staff in each of the collaborative groups were involved in product selection and trials, as well as in-services to ensure proper and effective use with each patient.

DECREASED RISK AND HEIGHTENED REWARD

As a result of interdisciplinary team collaboration, this facility has decreased the number and severity of pressure ulcers among patients at very high risk. Furthermore, there has been an increase in front-line staff engagement, which is where the greatest impact of these efforts is likely to occur. The organizational focus on pressure ulcer prevention and increase in interdisciplinary, proactive problem-solving and skin protection have been very valuable. RM

Amy Bratta, PT, DPT, has been an actively practicing physical therapist in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for more than 15 years. Her primary focus has been in the inpatient rehabilitation setting with people affected by spinal cord injuries.

Deborah Long, MSN, BSN, RN, CRRN, has been an actively practicing registered nurse in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for more than 18 years, certified in rehabilitation nursing through the Association of Rehabilitation Nurses (ARN) for 15 of those years. For more information, contact [email protected].