A useful strategy in industrial medicine.

By: Emily Monson, PT, and Larry Briand, MS, PT, ATC

A typical worker’s compensation patient arrives at a clinic with more than just the need for rehabilitation. Such patients are accompanied by a group of individuals who also need many things from you including assistance with work return strategies, obtaining a better understanding of ergonomic design in the workplace, body mechanics education, and consistent feedback about the progression of recovery. A clinician will quickly find that patient is required to be a resource to all, playing the role of case administrator, communicating with physicians, employers, insurance adjustors, and nurse case managers during care. This article will focus on the benefits of providing easy-to-understand Functional Progress Reports (FPRs) that are specific to an injury site. This kind of report will demonstrate comparative information on an injured worker’s job responsibilities and help guide all involved individuals with the journey back to work.

GETTING WORKERS BACK TO WORK

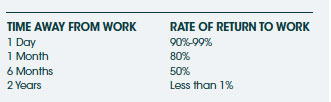

In today’s current environment of worker’s compensation claims, the treating therapist has an excellent opportunity to be actively involved in the overall case management of the injured worker. Objective data are needed during care to help with work return strategies, and therapists have the most accurate ability to portray this information by performing objective, functional testing and simulation in the clinic environment. With the high costs associated with worker’s compensation claims, companies are motivated to accommodate employees with work injuries to prevent lost time in the workplace. According to the National Safety Council, there

USING DATA FOR STRONG DOCUMENTATION

In an injured worker’s rehabilitation plan of care, documentation about the preparation strategies to return the worker to the tasks that need to be performed must be included. Just as an injured athlete would transition into more functional agility activities in preparation for a sport, physical and occupational therapists must become specialists in injured worker simulation and work reintegration. Holding a full understanding of the worker’s job details will often require an interactive and visual experience for the therapist. Going on-site at a company to learn about the specific demands of the job is a helpful and very useful way to learn how an “industrial athlete” needs to be best prepared for future full work return. On-site visits provide the rehabilitation specialist with an incredible opportunity to identify job demands, collect potential tools, understand equipment design, and observe the job tasks live. FPRs during care are created by simulating and reproducing these movement patterns in the clinic environment, and should be recorded in a way to update the patient, the referral source, and the payor about how the client is improving.

BENEFITS FOR STAKEHOLDERS

There are several benefits associated with bringing FPRs into an active plan of care. First, this is their value to the referral source. Employees are often assigned a particular work restriction from a physician who is conservative, and are often not tested to determine these limitations. Overly “safe” constraints protect the worker from doing too much too soon, but may not offer the correct insight about a patient’s current abilities. This prevents a company from finding work that can fall within the given restrictions. As stated earlier, the longer the time away from a particular job, the greater potential for the injured worker to never return. Providing regular updates to the physician on the client’s current abilities through simple FPRs will allow for restriction updates that better match the patient’s current abilities earlier in recovery. Functional reporting can be provided as frequently as every 2 weeks, and physicians often welcome this kind of information as it removes the burden of them having to create restrictions. Not only are the therapists providing regular objective updates to the referral source, but they are defining themselves as specialists in the management and treatment of injured workers. Another key player in an active plan of care is the worker’s compensation insurance carrier. According to the American Physical Therapy Association, one of the top payor complaints and reasons for denials is “documentation does not show progress.”4 The information provided in an FPR is also of great benefit to this group as the reports show progression throughout the plan of care. Demonstration of gains will assist with the authorization approval and coverage of services. Current status updates with FPRs also will create relationships with the adjustor or the assigned case manager, creating awareness of the clinician’s specialization in worker’s compensation management. Goals for the injured worker’s plan of care should be specific to the tasks of the job, eliminating the concerns by payors for coverage on activity that is not focused on work return needs. It must be remembered this is why the client is in the therapist’s care.

TASK PERFORMANCE: CONFIDENT AND CAPABLE

Finally, the most important person in this entire scenario is the injured worker. FPRs provide injured workers with awareness of their current abilities and areas of deficit, and give clinicians the opportunity to educate the patients about how the rehab process will evolve. This allows the opportunity to celebrate successes and gains in the recovery process. There is also significant time to practice and implement work movements specific to the worker’s job. This helps the patient become both physically and psychologically ready to return to work. Both the employee and the employer can feel confident in the given restrictions that are assigned because they have been practiced and accomplished. When FPRs result in the employee being cleared from all restrictions, all parties can feel comfortable and confident in work release, knowing that the individual is truly capable of the task. To perform an FPR, it is vital for a therapist to have an understanding of functional testing. Performing ongoing functional testing on the movement patterns required to perform the worker’s job helps track and show the progression toward work readiness. Work-specific simulation is also encouraged to be added during testing to identify the current abilities of the injured worker. As stated earlier, obtaining information by seeing the activity live through an on-site job visit will provide much of the information and potential materials needed. Functional Progress Reporting that focuses on testing the injured region and the tasks specific to an injured worker’s job benefits all involved in a worker’s compensation claim. It assists the primary physician in determining proper return-to-work goals, shows progression in the plan of care to payors who determine authorization and services approval, and helps the patient return to work quickly, while feeling physically and psychologically ready. More valuable than all of this, however, is being able to establish a strong awareness of the benefits of the therapist’s services, making the clinician’s practice a specialty clinic in the management of the injured worker. RM Emily Monson, PT, is the owner and director of Clear Lake Physical Therapy and Rehab Specialists, located in Clear Lake and Turtle Lake, Wis. She is also the co-developer and clinical instructor of Rehab Management Solutions’ Work Injury Program Initiative. Larry Briand, MS, PT, ATC, owns and operates a network of physical and occupational therapy clinics nationwide, including Clear Lake Physical Therapy and Rehab Specialists, and is the founder and CEO of Rehab Management Solutions, Sturtevant, Wis. He is also the Chief Visionary Officer of RMS’ Work Injury Program Initiative. For more information, contact [email protected].

Sidebar: Functional Capacity Evaluations Aligning Therapy Goals with Specific Job Function

Functional capacity evaluations (FCEs) are designed as standardized evaluations involving a range of functional tests of various work-related tasks. The evaluation’s primary purpose hinges on assessing the ability to participate in work based upon actual job requirements. To this end, FCEs created in conjunction with actual job demands can help springboard the plan of care toward return to work. Work-oriented goals can be developed through the use of a baseline functional status test performed early in the treatment process, according to Margot Miller, PT, vice president, Provider Solutions, for WorkWell Systems Inc, Duluth, Minn. Additionally, periodic functional tests offer “functional status updates” to stakeholders including the worker, physician, case manager, employer, and insurer, Miller points out. “The optimum scenario is when a functional job description of the worker’s current job is provided to assist development of the functional test. If no job description is available, an option is for the therapist to perform a job analysis to identify the job demands,” Miller says. A thorough, objective understanding of the worker’s job serves as a vital cog in the gears that drive a successful return to work. This allows for the forging of a treatment/conditioning plan and goals that align with the worker’s job function. Repeat functional tests can be used to assess the worker’s progress in reaching these goals. Miller underscores the idea that therapy goals must link to specific job functions. “The plan of care is not simply increasing the worker’s shoulder range of motion and strength,” Miller says. “Rather it is increasing the worker’s shoulder range of motion and strength so that the individual can perform the 40-pound waist-to-shoulder lift required of a bakery machine operator when preparing ingredients to make batches of dough,” she adds. – by Brittan West

References:

1. Injury Facts. Itasca, Ill: National Safety Council; 2013:62.

2. Waddell G, Burton AK. The Back Pain Revolution. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2004.

3. Waddell G, Burton AK, Main CJ. Screening to Identify People at Risk of Long-Term Incapacity for Work. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press; 2003.

4. Defensible Documentation Elements. The American Physical Therapy Association. Available at: http://www.apta.org/Documentation/DefensibleDocumentation/. Accessed February 20, 2014.